Different organisms have different lifespans. Under

normal circumstances, the cells that make up an organism will not survive that

creature’s death. Each cell type therefore has the same average lifespan as the

rest of the body. But is this inevitable? In particular, could neurons live

past their usual expiration date?

To test this, Italian researchers, led by Lorenzo

Magrassi of University of Pavia, relied on the different lifespans of

particular strains of mice and rats. Wistar rats can live for over three years,

whereas E12 mice hang on for an average of 18 months and a maximum of 26

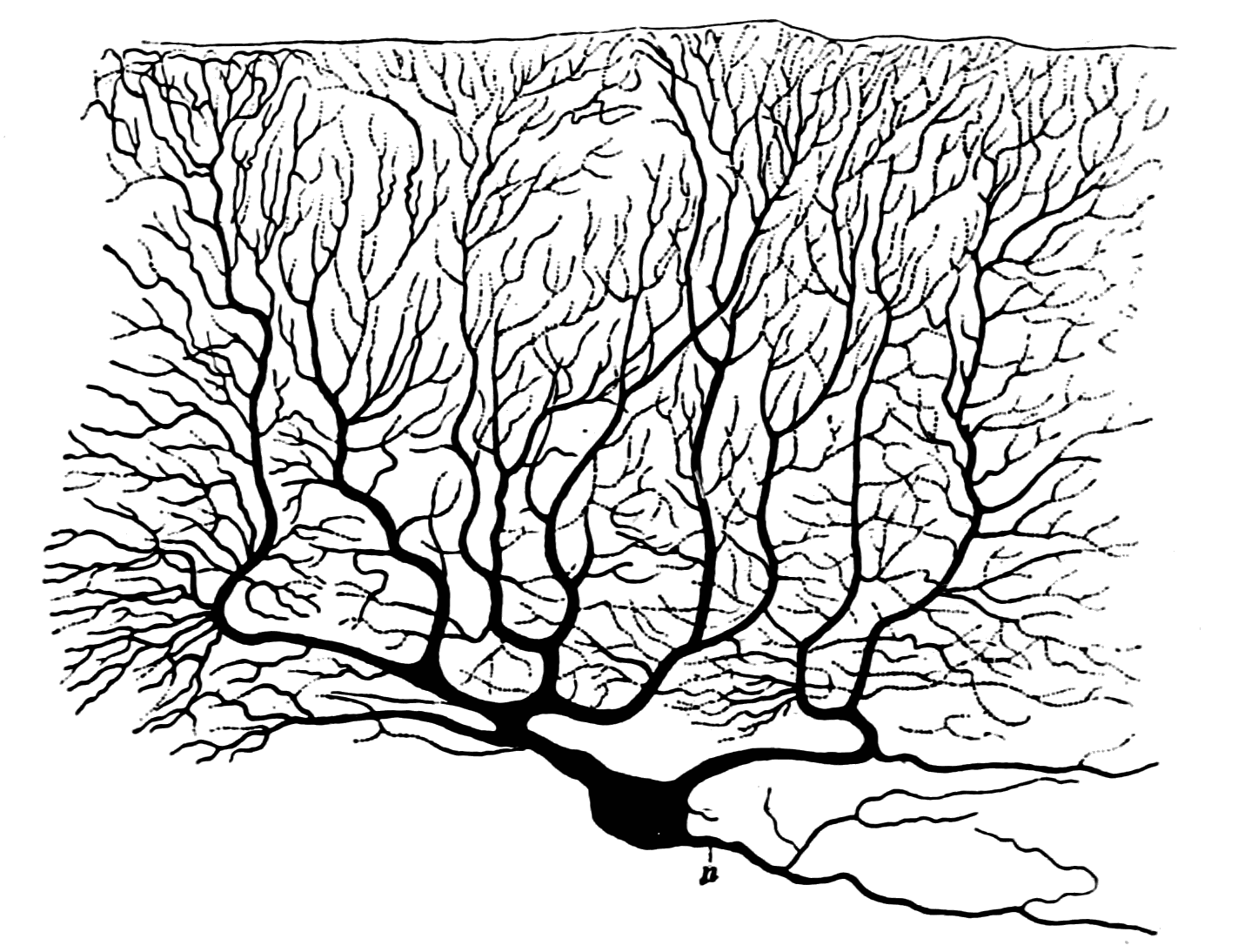

months. The researchers took neurons called Purkinje cells (PCs) from E12 mouse

embryos and grafted them into Wistar rat embryos. PCs were chosen because,

unlike other types of neurons, they are progressively lost as individuals age,

though in different proportions for different species. By the time a mouse dies

of old age it will have lost about 40% of its PCs. In contrast, a rat will have

lost only 11%.

To test this, Italian researchers, led by Lorenzo

Magrassi of University of Pavia, relied on the different lifespans of

particular strains of mice and rats. Wistar rats can live for over three years,

whereas E12 mice hang on for an average of 18 months and a maximum of 26

months. The researchers took neurons called Purkinje cells (PCs) from E12 mouse

embryos and grafted them into Wistar rat embryos. PCs were chosen because,

unlike other types of neurons, they are progressively lost as individuals age,

though in different proportions for different species. By the time a mouse dies

of old age it will have lost about 40% of its PCs. In contrast, a rat will have

lost only 11%.

The introduced mouse neurons did quite well in their new

homes, integrating themselves into the appropriate positions throughout the

brain. They were recognizable, however, because they remained slightly smaller

than their neighboring rat cells. In other words, the mouse PCs maintained their mouse characteristics.

Despite this, the mouse neurons survived for as long

as their host rat brains did, up to twice as long as they would have done if

they’d stayed in the mice. Perhaps more significantly, they did not decrease in

number as the hybrid rats aged. The grafted PCs looked like mouse neurons, but

they lived like rat neurons.

This could mean one of two things. Either the

type of brain in which a PC neuron finds itself dictates its longevity, or the brain type makes no difference (within reason), other than being alive. In the former case, mouse neurons will never live longer than two years as long as they reside inside mice. However, in the latter case, if we could coax a mouse into

living for three or more years, its PC cells would do just fine. If the same is true for humans, this could have implications for

human longevity. After all, we won’t want to live longer and longer if our

neurons have a strict shelf-life. If, on the other hand, our neurons can chug

along happily for double our average lifespans, then that would make it well worth working to

extend our lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment