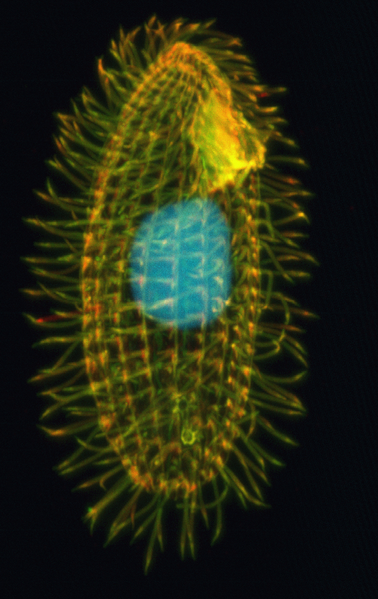

Meet Tetrahymena thermophila, a one-celled eukaryote with seven different sexes

(aka mating types). A cell of one mating type can successfully mate with a cell

from any of the other six mating types. And that’s not even the most interesting part of

this tiny creature’s sex life. It turns out that the mating types are assigned stochastically. According to first author

Marcella Cervantes of the University of California, Santa Barbara and her

colleagues, each cell’s mating type is effectively determined by random chance rather than by genetic history.

Our story begins with the observation

that T. thermophila have two nuclei

rather than one. One nucleus contains the ‘somatic’ genome, which is

responsible for the everyday running of the cell. The other, smaller nucleus

contains the inactive ‘germline’ genome. We keep our germline genomes in our

ovaries and testes. Within the germline genome are all seven pairs of sex

determination genes, one for each of the possible mating types. The somatic

genome contains only a single set of mating type genes, and it is this set that

determines what that cell’s sex will be.

This means that while each T.

thermophila cell contains all the genetic

material necessary to become any mating type, six of those genes are only found

in the quiescent germline genome. Only one set of mating type genes finds its

way into the actively expressed somatic genome. Here’s how that happens.

When two T. thermophila mate, they exchange genetic material with each other

(unlike with our unions, no third individual is created). Both cells

subsequently destroy their own somatic genomes. They then use material from

their germline genomes to construct new somatic genomes. But remember, the

germline genome includes genes for all seven sexes. During the process of

rebuilding the somatic genome, six of those mating types genes are excised so

that only a single one remains. There is an equal probability that any one of

the seven sets of mating type genes could be the last one standing.

This means that the sex of the cell

after a conjugation event is in no way related to the sex of that same cell

before that event. Meanwhile, the ‘reborn’ cell retains all the mating type

genes within its own germline genome so that it can continue the tradition.

You might be wondering why an

organism would need seven different sexes. Note that T. thermophila only mate under conditions of extreme duress. When you're in danger of starving to death, it’s best not to waste too much time looking for a suitable mate,

especially when you’re only 40 or so microns long and can only travel so far.

If you can successfully mate with six out of every seven potential partners you meet, so much

the better.

Credit: Robinson, R. (2006). Ciliate Genome Sequence Reveals Unique Features of a Model Eukaryote PLoS Biology, 4 (9) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040304

Article: Cervantes, M., Hamilton, E., Xiong, J., Lawson, M., Yuan, D., Hadjithomas, M., Miao, W., & Orias, E. (2013). Selecting One of Several Mating Types through Gene Segment Joining and Deletion in Tetrahymena thermophila PLoS Biology, 11 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001518.

No comments:

Post a Comment