An international team of astronomers, led by Emanuele Farina

of the University of Insubria in Como, has discovered a triplet of quasars. At

this point, you might be thinking, ‘this would be a whole lot more exciting if

I knew what a quasar was’. Or maybe that’s just me. In any case, writing this

article gave me a great excuse to learn more about quasars.

To begin with, ‘quasar’ is actually short for ‘quasi-stellar

radio source’. That is, it's a source of electromagnetic energy that’s

emanating from a star-like point.

In fact, a quasar is no kind of star but a supermassive black hole

surrounded by an accretion disk. For this reason, cosmologists now call them

quasi-stellar objects (QSOs), so I’ll switch to that terminology. As material

falls toward that black hole, massive collisions occur that form the accretion

disc circling the black hole and emit energy.

Actually, that understates the case quite a lot. QSOs are

among the brightest objects in the entire universe, each one putting out many

times the energy of an entire galaxy. This is why we can see them at all, since

they are also among the farthest objects, each at least three billion light

years away. QSOs are found at the center of some young galaxies. In fact, we often only know about that galaxy’s existence because we see the QSO in its center. Galaxies in which a supermassive black hole is actively munching on the

stars around it at a great enough rate to produce a QSO, are called ‘active

galaxies’.

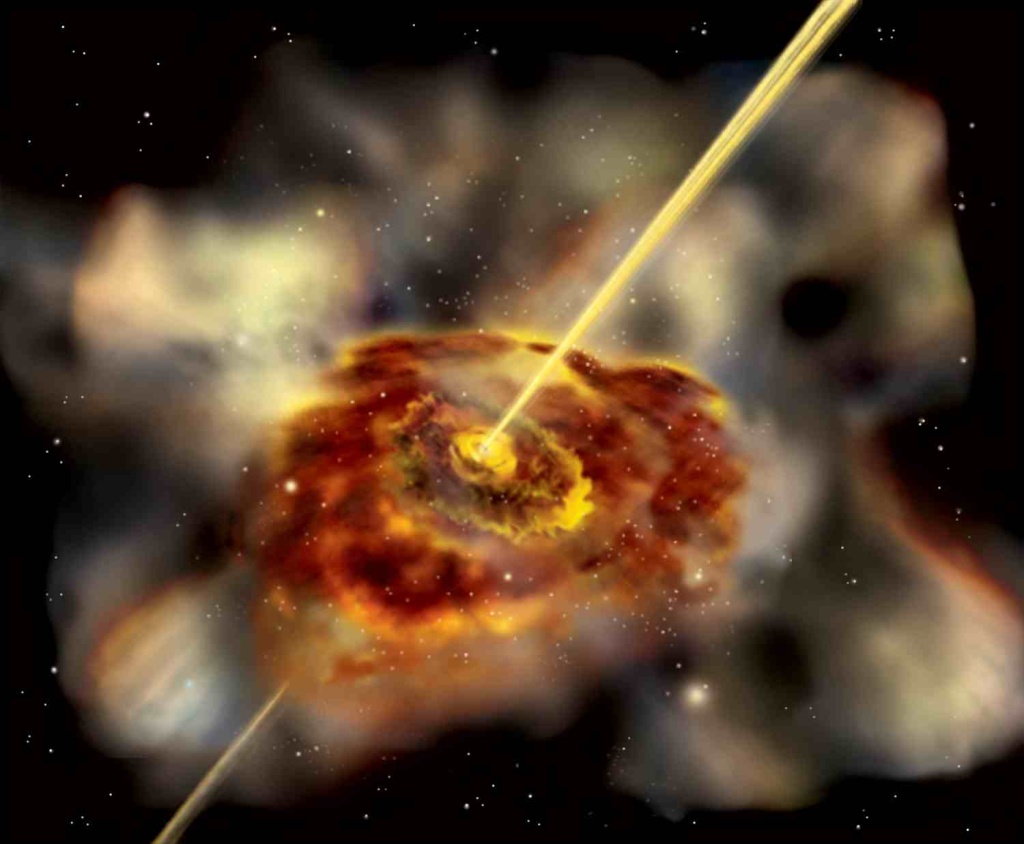

To make things even more interesting, all the energy from a

QSO is usually projected along a single line rather than equally in all

directions. You can see an artist’s rendition of this above.

So, at the center of a galaxy, you have a supermassive black

hole (with a mass of about a billion of our suns) that’s generating enough

energy to become an incredibly bright QSO. Under rare circumstances, possibly

due to the collision of two such galaxies, you end up with a binary system of

QSOs. Imagine how often three such galaxies combine. To give you an idea, this

is only the second triplet group of QSOs ever found (the previous one was

discovered over six years ago). Because of the placement of the three QSOs, the

authors suggest that two of them (B and C) interacted with each other first before the

third one (A) joined the grouping.

An infrared image of the triple quasar system QQQ

J1519+0627, made using the 3.5-m aperture telescope of the Calar Alto

Observatory. The three quasars are labelled A, B and C.

Credit: Emanuele Paolo Farina.

I think you can now see why this news is so exciting. Click the reaction boxes below to let me know if you agree.

You can learn more about QSOs here, here and here.

You can learn more about QSOs here, here and here.

How do we know they are relatively close to each other? How far away from Earth are they?

ReplyDeleteAll three QSOs are within 200 kiloparsecs (kpc) of each other, or about 650,000 light years. While that seems really far apart, the Andromeda galaxy is 780 kpc away from us. The researchers assume that any QSOs closer to each other than 500 kpc are too close to inhabit separate galaxies.

ReplyDeleteThe triplet is about 9 billion light years away from us.